The Scottish Baptist History Society asked Ian Balfour to give a Paper on this subject at their May 2006 meeting, held in Morningside Baptist Church, Edinburgh. As the proceedings of their six-monthly meetings are (regrettably) not published, the Paper is made available here.

Scroll down or click sections

(click numbers to open/close additional notes)

- Introduction

- Creation of first Elders’ Court

- First meetings of elders and deacons

- Election of 1878

- Elders, deacons and members

- Election of 1879

- Election of 1910

- Elders in Spurgeon’s Tabernacle

- Other Scottish Baptist churches

- Where are issues of principle decided?

- Changing social patterns

- Proposals for reform

- Separate meetings

- Election of 2000

- Election of 2005

- The role of the Church Secretary

- APPENDIX ONE: LETTER SENT TO MEMBERS IN NOVEMBER, 1910.

- APPENDIX TWO: MINOR ALTERATIONS IN PROCEDURE

Introduction

Back to top of page

Every five years between 1877 and 2000, the members of Charlotte Chapel elected elders and deacons to serve for the next quinquennium – Latin for ‘five years’, which puzzled some newcomers to the Chapel – after which elders, deacons and all appointed by them to other offices within the Church, retired en bloc and new elections were held. The structure was radically changed in 2005, where this paper concludes. There are still quinquennial elections, but they are now only for elders. What appears to be unique in Scotland is that until 1995, the elders and the deacons met together – had to meet together – for much of their business.

When the office of elder was introduced to the Chapel in 1877, it was modelled on the organisation that Charles Haddon Spurgeon and his people used at the Metropolitan Tabernacle, London. However, the Chapel’s Committee, which brought the recommendation to the Church, noted that ‘in Mr. Spurgeon’s Church the Deacons are entirely independent of the Elders, but in the circumstances of Charlotte Chapel the Committee … recommend that the Deacons … should act only in co-operation with the Pastor and Elders. As a practical means of securing this result … no meeting of the … Deacon’s court should be regular unless the Pastor and Elders receive a simultaneous invitation with the Deacons to be present – in short that the Pastor and Elders shall ex officio be members of the Deacons’ Court.’ From the beginning, the elders did attend throughout the meetings of the Deacons’ Court and contributed to them.

When the writer was first elected as an elder in 1965, the elders met for a sit-down meal at 6 pm in the Lower Hall – there was no Lounge then – on the first Wednesday of the month, followed by elders’ business from 6:30 to 8 pm. The deacons then joined the meeting, and deacons’ business was conducted on the basis that no new item was commenced after 9:30 pm. While it made a long evening for the elders, over three hours without a break, an impressive amount of ground was covered. This was achieved because immediately after the quinquennial election, every elder (20 of them) and every deacon (18 of them) was appointed – at their own request as far as possible – to serve on two of the Committees that did the day-to-day work of running the Chapel – evangelism, overseas mission, finance, building, Sunday School, music, The Record (the monthly church magazine) and several others – and so when any business came up, several of those present were familiar with the issue. Conversely, if a Committee was asked to do something, the elders and deacons on it knew the background and the context; if a Committee had some request to make to the Deacons’ Court, some of its members were there to see it through. Everyone saw the overall picture.

The Pastor chaired both meetings, but the Church Secretary had prepared the agenda for the elders and the Deacons’ Court Secretary had prepared the agenda for the deacons, and they guided the Pastor through the business. The Pastor knew that the only action required of him was to look after any spiritual issues that had been raised.

This pattern – although there is no reference to a meal beforehand – was established at the first meetings of the Courts after the 1877 election. The Elders’ Minutes often concluded with a phrase like, ‘The Elders proceeded to the meeting of the Deacons’ Court’ and one early Minute records a plea from the Minister, in the Chair, that they should try to finish the combined meeting by 10 p.m. Peter Grainger experimented from 1993 to 1995 with the elders meeting on the first Wednesday of the month and the deacons (which included as many elders as wished to attend) on the third Wednesday, but that didn’t work. After the 1995 election, everyone met together on the first Wednesday of the month from 6:30 pm (when the parking meters went off) to 7:45 pm, for Scripture reading and prayer and discussion about vision for future strategy and other relevant topics. The combined meeting concluded at 7.45 pm with a cup of coffee and a chance to chat informally for fifteen minutes, after which the elders and deacons met separately, to deal with the specific responsibilities allocated to them.

Creation of first Elders’ Court

Back to top of page

Owen Dean Campbell began his ministry at the Chapel on 5th July 1877. In November of the same year, a Special Church Committee, chaired by himself and composed of deacons and other members, met to consider the constitution of an Elders’ and Deacons’ Court and to overhaul the general organisation of the church work. As a result of its wide-ranging discussion, the committee made recommendations, which the congregation adopted. These may be summarised as follows:

- Elders to be elected as well as deacons, in order to secure the co-operation of younger members of the Church, the elders to assist the pastor in spiritual oversight, and the deacons to co-operate with the pastor and elders in temporal matters.

- The duties of the ‘Pastor and Elders, or Church Session’ – the phrase Church Session was regularly used to describe elders as distinct from deacons – were the maintenance of Public Worship, Baptism and the Lord’s Supper, custody of the Roll of Members, systematic visitation of members and especially the sick, ‘to edify and comfort believers – to arouse the careless – to encourage enquiries and generally to aid the Pastor in seeking after the Fruits of the Ministry’.

-

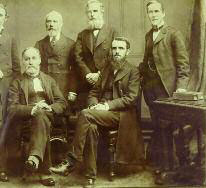

Owen Campbell and his five elders in 1883. Left to right: John E. Dovey (treasurer), John Anderson (secretary), R. A. Roberts, Alexander Picken, Campbell and John Walcot. The deacons were to manage the property and all finance except the Fellowship Fund, to appoint the Church Treasurer, Precenter, Chapel Keeper and to fix their salaries. The pastor and elders were ex officiis members of the Deacons’ Court, and were to be invited to all meetings of the Deacons’ Court.

- At the first Meeting of the Deacons’ Court, they were to appoint one of their number – I’ll come back to that phrase – to act as Secretary, with the duty of keeping Minutes of their meetings. ‘So, also, at the first Meeting of the Pastor and Elders they will appoint one of their number to act as Secretary and the Elder so appointed shall be considered the Secretary of the Church.’ Hence, seventy years after the constitution of the church, we have the first Minute Books, and the directive that the Secretary of the Elders’ Court should act as the Church Secretary – which remained the position, although the role of Church Secretary changed in the year 2000 and has now been discontinued, as described at the end of this paper.

- How many elders and deacons were to be elected on that first occasion was to be decided by the pastor and deacons, and for the future by the pastor and elders, ‘who, after consideration, shall submit a recommendation to the Church’.

- The rights of the Members to exercise ultimate control over the affairs of the Church was not affected, as elders and deacons were directly responsible to the Church for their actions.

The Church adopted all of these proposals and the policy bore fruit. With increased evangelistic effort, membership went up from 164 when Mr. Campbell arrived to 183, 212, and then 232 over the next three years.

The phrase ‘one of their number’ is underlined because some Baptist churches in Scotland have in recent years created elders for the first time, and in doing so have decided that neither the Church Treasurer not the Church Secretary should be elders, but should meet with the elders from time to time. It has regularly been suggested, in reviews of the duties of the office-bearers in Charlotte Chapel, that the Deacons’ Court Secretary, the Church Secretary, the Church Treasurer, the Convener of the Mission Board and others, as lay people and often in full-time secular employment, are sufficiently occupied with their designated role in the church and should not be expected to function as elders as well. This has been resisted by those who believe that all leaders, if they are designated ‘elders’, must be directly involved in pastoral care, as the New Testament definition of elder is one with pastoral oversight. There is merit in the opposition, because if the Treasurer, the Property Convener, the Magazine Secretary, the Mission Board Convenor, and many others with huge responsibilities, were also exempted – and why not? – there would be hardly anyone left to carry out the pastoral care. The whole matter was reviewed at the quinquennial election in the Spring of the year 2000, and reviewed again in 2005, as described below.

First meetings of elders and deacons

Back to top of page

Returning to 1877, when the newly-elected elders met for the first time, on 13th December 1877, they made arrangements for visitation of the sick and for their communion duties, planned to meet monthly on Sundays before the services for prayer, approved applications for baptism and membership for onward transmissions to the Church, revised the Roll and considered a resignation. They then went on to meet with the deacons, whose first agenda reflected their remit under the new Constitution. They appointed, and defined the duties of, the Treasurer, Secretary and Precenter, made arrangements for stewarding, received a Financial Report, fixed the salary of the caretaker, instructed refurbishing of the building and of the hymnbooks,

and arranged for the Sunday services to be advertised in the Scottish Baptist Magazine and in the local newspaper. They resolved to meet on the third Monday of every second month, the elders to meet first and then to be joined by the deacons.

Election of 1878

Back to top of page

The election of 1878 – the second under the new arrangement – is noteworthy for two reasons. (There is no record of how the 1877 election was conducted, because no Minutes were taken until the new-style Courts actually met.) While Charlotte Chapel adopted and adapted the practice of the Metropolitan Tabernacle in creating an eldership, the Chapel Committee either did not know about, or did not give much weight to, the views of C.H. Spurgeon on the method of appointment, namely that: In my opinion, the very worst mode of selection is to print the names of all the male members, and then vote for a certain number by ballot. I know of one case in which a very old man was within two or three votes of being elected simply because his name began with A, and therefore was put at the top of the list of candidates.’

Considering that the members would have prayed about the election, it may seem irreverent to suggest that the layout of the ballot paper influenced the result, but the

fact is that Messrs Cairns, Coutts, Davis, Dovey, Johnston, and Urquhart were elected and Messrs Weddell and Young were not.

The committee preparing for the 1995 election in the Chapel were seriously asked to consider printing the men’s names in reverse alphabetical order on alternating elections, but the suggestion was not taken up. Another ‘hardy annual’ – or ‘hardy quinquennial’ – issue in the Chapel is whether or not to put an asterisk against the names of existing office-bearers, on the first list. With 173 names on the 1995 list of men eligible for nomination, it was assumed, probably correctly, that if the existing incumbents were asterisked, some members would simply skim through the list and select the marked names. On the other hand, when, as in 1995, this was not done, several members protested that they were satisfied with the performance of the existing Courts and were concerned that without guidance, they might miss out someone who deserved to be re-elected. The election committee responded that if electors cannot put faces to names, they should not be voting for them. As a working compromise, which probably had the best of both options, a brief biography of all candidates for the final ballot was distributed with the papers and at the same time, photographs of the candidates, suitably named, were displayed in the Lounge. Those from smaller churches may find it difficult to credit, but in a congregation the size of the Chapel even members of some years perused the display of photographs and said

The committee preparing for the 1995 election in the Chapel were seriously asked to consider printing the men’s names in reverse alphabetical order on alternating elections, but the suggestion was not taken up. Another ‘hardy annual’ – or ‘hardy quinquennial’ – issue in the Chapel is whether or not to put an asterisk against the names of existing office-bearers, on the first list. With 173 names on the 1995 list of men eligible for nomination, it was assumed, probably correctly, that if the existing incumbents were asterisked, some members would simply skim through the list and select the marked names. On the other hand, when, as in 1995, this was not done, several members protested that they were satisfied with the performance of the existing Courts and were concerned that without guidance, they might miss out someone who deserved to be re-elected. The election committee responded that if electors cannot put faces to names, they should not be voting for them. As a working compromise, which probably had the best of both options, a brief biography of all candidates for the final ballot was distributed with the papers and at the same time, photographs of the candidates, suitably named, were displayed in the Lounge. Those from smaller churches may find it difficult to credit, but in a congregation the size of the Chapel even members of some years perused the display of photographs and said

‘so is that his name? I have often seen him welcoming people at the door, but I never knew his name’.

The second point which deserves comment, about the 1878 election, is the invitation, never repeated as far as can be traced, for members to add any other name of their own choosing to the ballot paper.

While every male Member of the Church is eligible for either office, the Voting-paper contains the names of five Members who have consented to allow themselves to be nominated for the office of Elder; and of eight Members who are willing to act in the office of Deaconsix to be elected.

Members will record their votes by Placing a mark (X) against the names they prefer (on the left-hand side); and should any Member wish to vote for any of the Brethren not mentioned in the Voting-paper, they are at liberty to add such names to their own Voting-list, taking care also to place a mark (X) against the name or names so added. Whether anyone did, we do not know, but only the recommended candidates were elected. The option became unnecessary when elections were split into two parts, as described below, with the names of all male members appearing on a nomination paper, preliminary to the final ballot.

Elders, deacons and members

Back to top of page

Working relations between elders and deacons were good, and some reasons for that are suggested later, but two decisions about the church organ, one in 1879, and the other a century later in 1973, illustrate how the elders, deacons and the congregation

relate to one other. In the summer of 1879, the elders, having responsibility for the conduct of worship, ‘agreed that the harmonium should be used at both services on the Lord’s day’ – until then, singing had been led by the precenter. When this decision was conveyed to the deacons, they decided that ‘the present harmonium was quite insufficient to lead the singing of the congregation and that many members’ (presumably also dissatisfied with the harmonium) ‘had promised liberal subscriptions if the Deacons’ Court sanctioned the purchase of a suitable

instrument’. With one deacon dissenting, the Court appointed a group to collect funds, and, as soon as £30 was in hand, with reasonable expectation of more, to select and purchase an instrument at a price not exceeding 70 Guineas. In other words, the elders saw the need for a change in the pattern of worship; the deacons took on board the practical implications; the congregation supported the project and three months later a new harmonium was installed.

Nearly a century later, in 1973, its successor, installed in 1928, was showing signs of terminal illness. Regularly and always without warning, the bellows ceased to bellow, leaving the organist to precent until repairs could be carried out. As there was no ‘spiritual principle’ involved, but merely the practical question of a replacement, it was to the Deacons’ Court that the musicians made their request for action. There were three possibilities – to repair the Pipe Organ at a cost of £8,000, to purchase an Allen Digital Computerised Organ, tonally equal to a Pipe Organ but costing only £5,000, or to install a Hammond Organ, cheaper still at £2,750, but with poorer tonal effect. By 19 votes to 10, (there were a lot of apologies that evening) the deacons voted to purchase a new organ rather than to repair the existing one. 15 then voted for the Allen organ and 14 for the Hammond. The pastor, Derek Prime, suggested resolution by a method which he had proved in the past, namely that a Fund should be opened, the congregation advised of the options, and that the monies received by the last Sunday in July 1973 would determine which instrument was purchased. This was agreed, and the congregation voted with their pockets, giving or promising just enough for the ‘cheapie’. This still serves today – now supplemented by a keyboard and/or a band.

Election of 1879

Back to top of page

After only two annual elections, in 1877 and 1878, the elders decided that one year was too short for the good of the Church and proposed elections every five years. The pastor, on behalf of the elders, explained the position to the deacons in

November 1879, saying that before going to the Church with their recommendation, the elders ‘were desirous of hearing the opinions of their coadjutors on the subject. The deacons agreed to acquiesce in the recommendation and the matter was referred to the Elder Session’ (as mentioned, the deacons regularly referred to the elders as ‘the Session’) ‘to arrange for its being brought before the Church’. Things moved quickly in those days. The pastor gave notice to the congregation on the first Sunday in December ‘that on the following Sunday he would propose the re-election of all the present office-bearers for a term of five years’. Nothing more appears in the Minute Books until 1885, when six elders and eight deacons were elected, and so it continued in 1890, 1895, 1900, and 1905.

Election of 1910

Back to top of page

The next document worth mentioning is the letter to all members, over the signature of the Church Secretary, inviting them to participate in the elections of 1910. It is reproduced in full as an Appendix, but the key features were: The number of elders to be elected was six, and the number of deacons ten.

The term of office was, as before, five years. The principal duties of the elders were:

- Visitation, under the direction of the pastor;

- Attendance on the ordinances of the Lord’s Supper and Baptism;

- Conduct of the Weekly Prayer-Meeting in the absence of the pastor;

- Distribution of the Fellowship Fund. The duties of deacons were management of the Property and Funds of the Church, except the Fellowship Fund.

A list of all eligible male members was attached to the voting papers for elders, which took place first. Voting Papers for deacons were not sent out until the results of the eldership elections were known, so that anyone who had voted for an elder would know whether or not he had been elected and, if not, could vote for him as a deacon – a practice which continued into the twenty-first century but has now been changed. The documentation sent to members at quinquennial elections referred to the New Testament qualifications of elders and deacons and made clear that the two offices are complementary, not necessarily a progression. It is however difficult to persuade people that the office of deacon is not a step on the way to the office of elder. Indeed, when the writer was first nominated as an elder in 1965, never having been a deacon, he was approached by the late Bert Aitken, who above almost anyone else knew and understood the Chapel, and he said, ‘I want to let you know that I have nominated you on this occasion as a deacon, not an elder, because I believe that a man should serve his apprenticeship as a deacon before he becomes an elder.’

Going back to the election of 1910, when the membership was 638, to operate with only six elders and ten deacons does not seem a lot for a church which had experienced several years of growth and revival. In 1995 the office-bearers thought that they were stretched with 22 elders and 18 deacons for a membership of 760. In fact, when the 1910 Courts first met, the elders co-opted one additional elder and the deacons co-opted two additional deacons, for which there was authority in the 1877 scheme. This was reported verbally to the congregation, followed up by a rather laconic entry in the January 1911 Record:

The election of office-bearers for the next five years has now been completed, and the result is ‘no change.’ Deacons Aitken and Craig have become elders, and the vacant places in the Diaconate filled by Messrs McLaren, F. Clark and Linklater. That all the existing Elders and

Deacons were re-elected shows the church’s confidence in the brethren. The work is oftentimes tedious and binding, and it requires no little self-sacrifice on the part of business men to devote so much of their time to the routine of the church. Let us remember our officebearers in prayer that they may worthily fulfil the offices to which they have been called.

Elders in Spurgeon’s Tabernacle

Back to top of page

As subsequent quinquennial elections followed much the same pattern, there is little point in analysing the conduct or the result of the next seventeen elections. Something will be said later about attempts to improve the system, but how did Spurgeon’s Tabernacle came to its practice, which the Chapel more or less adopted in 1877?

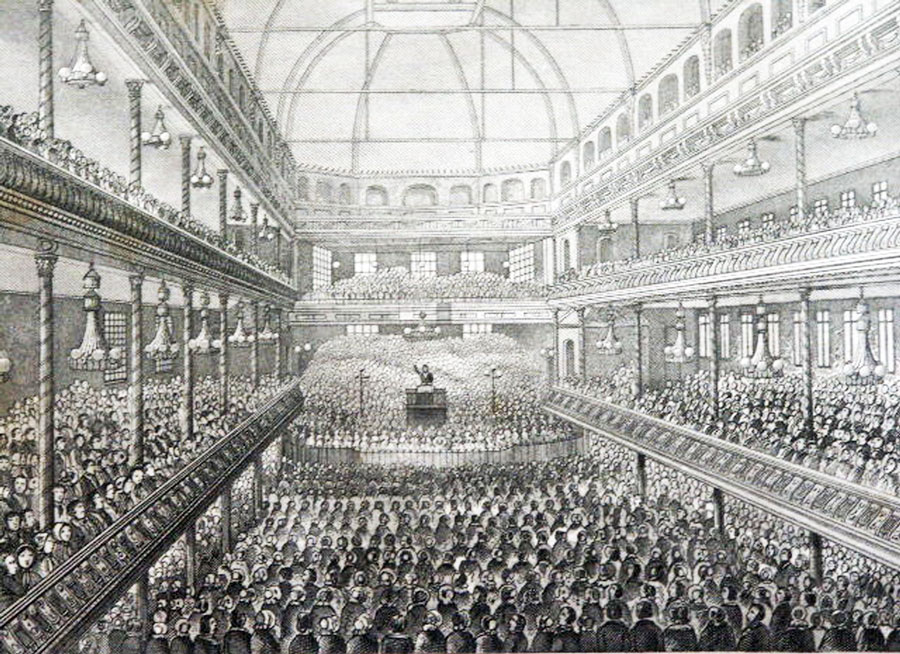

Charles Haddon Spurgeon accepted a call in 1854 to the New Park Street Church, Southwark, London, where about 200 were worshipping in a chapel with accommodation for 1200. The congregation traced its origin to 1652, and operated with a diaconate – no elders. Three years later, as Mr. Spurgeon’s preaching was attracting great numbers, they decided to erect a Tabernacle to seat 3000, but it was during the New Park Street days that elders were introduced.

‘When I came to New Park Street, the church had deacons, but no elders; and I thought, from my study of the New Testament, that there should be both orders of officers. They are very useful when we can get them – the deacons to attend to all secular matters, and the elders to devote themselves to the spiritual part of the work; this division of labour supplies an outlet for two different sorts of talent, and allows two kinds of men to be serviceable to the church and I am sure it is good to have two sets of brethren as officers, instead of one set who have to do everything, and who often become masters of the church, instead of the servants, as both deacons and elders should be.

As there were no elders at New Park Street, when I read and expounded the passages in the New Testament referring to elders, I used to say, ‘This is an order of Christian workers which appears to have dropped out of existence. In apostolic times, they had both deacons and elders, but, somehow, the church has departed from this early custom. We have one preaching elder – that is, the Pastor – and he is expected to perform all the duties of the eldership.’ One and another of the members began to enquire of me, ‘Ought not we, as a church, to have elders? Cannot we elect some of our brethren who are qualified to fill the office?’ I answered that we had better not disturb the existing state of affairs, but some enthusiastic young men said that they would propose at the church-meeting that elders should be appointed, and ultimately we did appoint them with the unanimous consent of the members. I did not force the question upon them; I only showed them that it was Scriptural, and then of course they wanted to carry it into effect.’

The record of the annual church meeting on January 12, 1859, reads:

‘Our Pastor, in accordance with a previous notice, then stated the necessity that had long been felt by the church for the appointment of certain brethren to the office of elders, to watch over the spiritual affairs of the church. Our Pastor pointed out the Scripture warrant for such an office, and quoted the several passages relating to the ordaining of elders: Titus I. 5, and Acts 14. 23 – the qualifications of elders; 1 Timothy 3. 1-7, and Titus 1. 5-9 – the duties of elders; Acts 20. 2 8 – 3 5, 1 Timothy 5. I 7, and James 5. I 4; and other mention made of elders: Acts 11.30, I5 4, 6, 23, 16.4, and 1 Timothy 4.1 4.

Whereupon, it was resolved -That the church, having heard the statement made by its Pastor respecting the office of the eldership, desires to elect a certain number of brethren to serve the church in that office for one year, it being understood that they are to attend to the spiritual affairs of the church, and not to the temporal matters, which appertain to the deacons only.’

Mr. Spurgeon said (above) that it was from ‘my study of the New Testament, that

there should be both orders of officers.’ He would also, although he did not mention

it in this context, have observed churches with elders and churches without elders,

because almost from the beginning of Baptist life in England, both forms of church

government were practiced. This is not the place to trace the pilgrimage of John

Smyth, who wrote in 1608 that:

the triformed Presbyterie consisting of three kinds of Elders viz. Pastors Teachers Rulers is none of Gods Ordinance but mans devise. Wee hould that all the Elders of the Church are Pastors: & that lay Elders (so called) are Antichristian.

That not everyone – including Spurgeon – read the New Testament in that way is illustrated by two events which just happened both to take place in 1679. In that year, the General Baptists set out their beliefs in their Orthodox Creed.

The only person designated elder was the pastor of the local Church, who was assisted by deacons, but he alone baptised and presided at the Lord’s Supper. However, also in 1679, a layman in the Broadmead Church in Bristol, a Particular Baptist Church constituted in 1640, made a Will which was published on his death a few years later. He willed the bulk of his considerable estate for the better education of the ministry, but made other references to the Broadmead church, which functioned with a minister, elders and deacons – the testator himself being one of the lay elders in the Broadmead Church.Reflecting on his new style of church government, Spurgeon recorded:

‘My elders, usually about twenty-five in number, have been a great blessing to me; they are invaluable in looking after the spiritual interests of the church.’

As to the succession of office-bearers, Mr. Spurgeon, ‘made it a rule to consult the existing officers of the church before recommending the election of new deacons or elders, and I have also been on the look-out for those who have proved their fitness for office by the work they have accomplished in their private capacity. In our case, the election of deacons is a permanent one, but the elders are chosen year by year, though they usually continue in their office for life. This plan has worked admirably with us, but other churches have adopted different methods of appointing their officers. In my opinion, the very worst mode of selection …’ (and he criticised ballots, as already quoted . Turning from seventeenth and nineteenth century English practice, what has been the

recent practice in …

Other Scottish Baptist churches

Back to top of page

Why has Charlotte Chapel continued, apparently without question, to have both elders and deacons when nearly every other Baptist Church in Scotland, certainly then and largely even now, works with a pastor (or a pastoral team) and deacons (only). The writer first became aware how strongly some ministers feel about the issue, over the tea-table of the manse of the Govan Baptist Church in 1952. The minister, James Taylor, had invited an inter-denominational group of students to participate in a Saturday evening rally and to meet and finalise the arrangements over tea. Christopher Anderson would not have approved, but conversation on these student occasions in the 1950’s turned, more often than not, to either or both of the subjects which were taboo in Mr Anderson’s manse on Monday evenings – modes of baptism and forms of Church government.

On this particular occasion, it was the latter. One of the students, a member of Charlotte Chapel, was extolling the virtues of leadership by elders and deacons. Asked by Mr Taylor to provide a New Testament basis for this, the young man said that it was self-evident from the opening verse of the Epistle to the Philippians, in which the Apostles Paul and Timothy addressed three groups, ‘the saints in Christ Jesus which are at Philippi, with the bishops and deacons: Grace be unto you, and peace.’

The New International Version has ‘To all the saints in Christ Jesus at Philippi, together with the overseers and deacons …’ but in 1952, even students thought in, and quoted from, the Authorised Version – it was only when the whole Bible, as opposed to the New Testament, came out in the Revised Standard Version later that same year, that many moved away from the 1611 translation. Mr Taylor quizzically raised one eyebrow and asked where the minister came into this pattern? The bold student replied that the minister was a ‘preaching elder’, and that the verse in Philippines clearly demonstrated the New Testament pattern – faithfully followed by Charlotte Chapel – was elders (which included the minister), deacons and church members. Mr Taylor’s face was a study, but he was neither the first nor the last Baptist minister to argue strongly, indeed forcefully, that the minister is the presentday equivalent of elder and that the remaining leadership should be designed as deacons and deacons only. The phrase ‘a preaching elder’ was beloved and promoted by Sidlow Baxter, minister at Charlotte Chapel from 1935 to 1953, so it was not surprising that the student just mentioned felt so strongly about elders and deacons.

Mr. Taylor’s view of minister, deacons and congregation – without elders – was assumed, apparently without question, in the Deacons’ Handbook, published by the Baptist Union of Scotland.

It describes leadership in a Baptist church, including worship, communion, baptism, membership, visitation, evangelism, prayer, discipline, and everything else, without mentioning the word elder.

Is it a reaction against the prominence given by the Church of Scotland to elders – if the established church was for it, Baptists were instinctively against it? Is it because Baptists shy off using the name elder where the leadership includes women – lady deacons are acceptable, but is there Biblical objection to lady elders?

Is that why some churches call their leadership team ‘Area Pastors’ rather than elders? Or is it lack of numbers, because if a small congregation is hard put to find sufficient leaders, it can do without the complication of dividing the work into two areas? Is it fear of a ‘kitchen cabinet’ around the minister, especially if not directly and regularly elected – because there is a strong argument for appointing elders for life, as in the National Church? Have some had bad experience of heavy-shepherding in groups where the leaders are designated elders? Is there a feeling that the congregation is accountable in some way to elders, whereas deacons are believed to be accountable to the congregation? Or does it go back to the reasons which made Christopher Anderson adopt the style of government of ‘English’ Baptists – so called even if they met in Scotland – over against the plurality of elders in Scotch Baptist churches and all that followed from their dogmatic insistence on the role of elders? Or is it more practical than theological – it can be divisive. One of our churches recently unanimously approved the principle of elders, but fell out grievously on who should be appointed and the whole idea has been shelved. Even if you believe, like Spurgeon, that eldership is a scriptural office for the church today, if two principles conflict, the higher principle must prevail, and surely the unity of the church is more important than how the leadership is designed. Perhaps that really is the answer to my question, because if, as the Deacons’ Handbook describes the situation, if deacons are in fact functioning as elders also, does it really matter what they are called?Where are issues of principle decided?

Back to top of page

Where have matters of principle, particularly spiritual issues, been discussed and decided since the creation of elders in Charlotte Chapel in 1877? Before the reorganisation in the year 2000, the answer was emphatically with the elders sitting alone as the Elders’ Court. On Wednesday 18th November 1998, the third Wednesday of the month, the elders and deacons met together for an hour and a half of prayer – no business, only a brief introduction to the topic on which prayer is to be focussed. On that Wednesday, it was the future of the Chapel’s outreach in the district of Niddrie in Edinburgh. The elders had met an hour earlier, before the deacons arrived – the first time they have done this under the ‘Third Wednesday’ time of prayer – in order to finalise their recommendation to the half-yearly meeting of members, due shortly. (The policy had already been thoroughly thought through over an extended period – major new decisions are not made after one hour of discussion.) The deacons were not involved in formulating that recommendation. There was, without dissent, a clear view that the policy of mission was a ‘spiritual issue’, and therefore one for the elders. The deacons were immediately informed, so that all could pray intelligently about the consequences – hence the need to meet an hour before the usual time – but there was no doubt that the spiritual leadership – that is the elders – should decide what to recommend to the members.

How different things were, when the Sunday School teachers proposed, in 1919, that the time had come to form a Scout Troop in the Chapel. It was the deacons (who of course included the elders), not the elders (meeting alone), who discussed the request. Since the previous minister, Joseph Kemp, had been strongly opposed to creating uniformed organisations within the Church, it would have been self-evident to late twentieth-century office-bearers, that the elders should consider the principle before it went to the deacons. No one in 1919 thought it unusual that the paper from the Teachers went straight to the deacons (including the elders) and they warmly approved the proposal.

Insert left: George Davidson, Donald Cormack. Insert right: Norman Hunt, John McGuiness Back row: David Murray, Tom Sim, Jack Oliphant, John Coutts, John Balmer, Robert Hadden, David Petrie, Peter Armstrong, Jim Hudson, George Rae, William Tullis. Second row: William Somerville, David Wallace, Robin White, Oscar Barry, Robert Findlater, William Tregunna, Douglas Macnair, Jim Cossar, Jack Cochrane, Charles Steele, John McGregor, Tom Currie. Front row: Jim Purves, Jim Paterson, Peter Murray, Robert Clark, MacDuff Urquhart, Gerald Griffiths, Robert Aitken, David Blair, George Rae, David Jenkins, John Whitlie.

Of more significance is that time and again, in the unhappy ecumenical debates of the 1950’s and early 1960’s, it was in the Deacons’ Court that the issues were debated and decisions made. Alan Redpath, minister at the Chapel from 1962 to 1966, frequently expressed to the writer his concern – perhaps the writer was too sympathetic a listener – that elders stayed silent during discussion in the Elders’ Court, which met first, and then were outspoken, sometimes for but sometimes against, when the elders’ recommendation was taken to the deacons. This was deliberate, as Robert Aitken acknowledged to the writer when the writer asked him about this, because these experienced men knew that what the deacons thought of the proposition was what really mattered.

Those with secular management training have expressed concern, from time to time, that there appeared to be two executive bodies in the Church, and that this is bad in principle. All that the writer can say is that in the thirty-five years that he served on the Courts, there was no problem in practice about ‘who does what’. From time to time, for example when the elders reported, for information, that they had agreed to an outside organisation issuing tickets for a day conference, with an admission charge printed on the face of the ticket – regarded as a spiritual issue for the elders, because many felt strongly that all activities on church premises should be free of published admission charge – the deacons gently reminded the elders that letting the property was the responsibility of the deacons. The point was graciously made and graciously taken. This is not a uniquely Chapel problem, because C.H. Spurgeon recorded in his memoirs, with a chuckle, an incident which he overheard, unseen:

I heard one of our elders say to a deacon, ‘I gave old Mrs. So-and-so ten shillings the other night.’ ‘That was very generous on your part,’ said the deacon. ‘Oh, but!’ exclaimed the elder, ‘I want the money from the deacons.’ So the deacon asked, ‘What office do you hold, brother?’ ‘Oh!’ he replied, ‘I see; I have gone beyond my duty as an elder, so I’ll pay the ten shillings myself; I should not like ‘the Governor’ to hear that I had overstepped the mark.’ ‘No, no, my brother,’ said the deacon; ‘I’ll give you the money, but don’t make such a mistake another time.’‘

Perhaps the happy relationship between the ‘two executive bodies’ in the Chapel stems from the fact that so much of the business – until recently, all deacons’ business – was conducted in the presence of the full, combined, Court. Elders were far from reticent when sitting ex officiis as deacons, so much so that both Alan Redpath and Derek Prime had to draw out contributions from the deacons and gently discourage the elders from dominating the discussion in the combined Court.

Policies do, however, change. When Alan Redpath, realising that his health would not permit him to carry on his duties as pastor with the energy which he wished, tendered his resignation in the spring of 1966, there was no dissent to the motion that ‘the Deacons’ Court be appointed the Vacancy Committee’. At the time, it seemed the most natural thing to do. However, when Derek Prime tendered his resignation for the same reason in 1986, and when it was again suggested that the Diaconate should act as the Vacancy Committee, or ‘Search Committee’ as had become the more popular phrase, the deacons themselves responded that since the elders had been appointed by the Church to the spiritual leadership of the congregation, it was for the elders alone to seek for a new pastor. Incidentally, on both occasions the Courts strongly resisted any suggestion of co-opting others, either as individuals or as representing organisations within the Church. The justification, based on past experience, was that selection of a manageable number from the large congregation would cause more tension than the benefits which wider representation would bring. In the more democratic spirit of 1986, when questions were asked about the female point of view, the answer that ‘the elders would consult with their wives privately’ was accepted.

Changing social patterns

Back to top of page

As with society at large, so with office-bearers in Charlotte Chapel – attitudes have changed remarkably since the mid 1960’s. Three illustrations will suffice – dress code, ‘traditions of the elders’, and commitment. All are minor in the context of Church history, but whenever the present generation says – ‘you can’t be serious’ – and means it – it may be worth recording behaviour which was taken for granted in the 1960s. Sea-changes in social attitude have taken place in the Chapel, of which the dress expected of elders at communion is one. In 1965, it was de rigeur to wear black jacket and striped trousers for the monthly communion service. One able man declined to let his name go forward for election as an elder because he did not possess such a suit and could not afford to purchase one. Some years later, after a senior elder had deliberately turned out in a lounge suit, Bert Aitken tabled a question for the next Court, as to whether it was acceptable to go onto the platform for communion in a lounge suit. In the discussion which followed, some relaxation of standards was reluctantly accepted, and in due course an influx of younger men, who could have afforded formal dress but who saw no occasion to purchase it only for communion duties, made the point academic.

Similarly, where elders sat during the Sunday services was deemed significant. Whether the practice came Spurgeon’s Tabernacle is not known, but C.H. Spurgeon insisted that his office-bearers sat behind him on the platform on Sundays, to demonstrate solidarity and support. In the Chapel of the 1960’s, as in many parish churches of the day, the front pew on either side of the pulpit, facing inward to the pulpit and sideways to the congregation, was reserved for the elders who sat, without family or friends beside them, in a row – many in formal dress and with a particularly solemn demeanour. Visitors remarked on this, not always flatteringly. Believing that families should worship together, especially since children of all ages remained in for the entire Service in those days, the writer and others declined to join the ‘front

bench’. As that generation retired, they were not replaced in that location, but, again, this was lamented from time to time by those who believed there were ‘traditions of the elders’ to be upheld.

A third illustration of changing social patterns is more significant, because it reflects a national trend. Over the last decade or so, comment has frequently been made that both in church and secular voluntary organisations, it is difficult to get people to commit themselves to regular duties. The Court in 1965 was run with a combination of spirituality, business efficiency, dedication and military efficiency

which could not be reproduced today, even if one wished to reproduce it. That is not to complain that ‘things aren’t what they used to be’, but organisations across society have noted how few people nowadays ‘join’ anything, although they are happy to ‘attend’. Whereas the election of elders and deacons in Charlotte Chapel in 1965 was keenly contested, indeed competitive, and there were many more candidates than vacancies, by 1985 the Chapel was unable to find enough candidates to compile a ballot paper. The system was taken by surprise and every nomination for elder – stage one in the election process – was declared elected because there were only 22 nominations for 22 vacancies. It was the embarrassment of some of the candidates themselves, who felt they were not ‘properly’ appointed just because twenty people out of seven hundred had nominated them, which led to a revision of the rules, and now the names, even if there are less than the number required, are submitted to the congregation as stage two, with a certain percentage of votes required for election.

Proposals for reform

Back to top of page

In light of that, this may be the place to say that after every one of the seven quinquennial elections in which the writer has been involved, and sometimes in between elections as well, someone has said that there must be a better way of appointing office-bearers. The 1877 arrangement was the outcome of a comprehensive review by a specially appointed Committee. Various review bodies in the 1970s and 1980s made recommendations, but the Courts or the congregation decide to keep the status quo. When Alan Redpath became minister in 1962, and learned that there would need to be an election in the Spring of 1965, he set in hand, and chaired, a Committee to consider reform of the Court system. He described the methods of election as cumbersome and protracted. It produced a detailed report, which the Courts considered, thanked the Committee for its work and passed on to other business. In 1984, the deacons – i.e. all the office-bearers meeting together – ‘considered various suggestions which had been made to amend the structure and … agreed to retain the present structure.’ After another full review in 1993, the 1995 election was conducted in more or less the same way as the 1910 one.

Separate meetings

Back to top of page

The 1995 election proceeded smoothly, but the 22 elders and 18 deacons did not immediately launch, as their predecessors had done, into appointing committees. They embarked on a careful appraisal over the summer months of their spiritual gifts – not just as they imagined them, but as others saw them. They then formed themselves, at the end of 1995, into thirteen ‘ministries’ (deemed to be a more appropriate word than ‘committees’, in an attempt to distinguish church business from secular activity) to promote the various aspects of congregational life. Every ministry was led by a ‘coordinator’, rather than the traditional ‘chairman’ or ‘convenor’.

The other major change was that after the 1995 review, it was decided that the elders and the deacons should meet separately. How did they square that with the 1877 directive? The Chapel has no written Constitution; it works on precedent, decisions of Church meetings, accepted practice and consensus. When the structures of 1877 were put in place, the undertaking was given to the congregation that ‘ultimate control over the affairs of the Church would remain as at present, and both the elders and the deacons would be directly responsible to the Church for all their actions’. That remains true, but the definition of what is ‘ultimate’ requires a delicate balance between responsible leadership and proper accountability. Elders, deacons, the Pastoral Team, Chairmen of Committees/Ministries were constantly making decisions which affected the life of the Church. Guidelines as to what they may do without reference to the congregation are of some help, but if they took many matters to a congregational meeting, some of the members would say, ‘Why ask us – we elected elders and deacons to decide things like that – don’t complain if there is a derisory turn-out at members’ meetings when you waste our time on matters like that’. On the other hand, when they do take decisions, other members complain that they should have been consulted – ‘it’s the principle that matters’. The official explanation is that when the congregation elects elders, it re-endows the elders with their traditional responsibilities, like admission to membership, which in most Baptist churches would

be brought to the members, often at the close of a Sunday morning service.

Election of 2000

Back to top of page

After much discussion, it was agreed to appoint a small number of ‘Ministry Elders’ and sufficient ‘Pastoral Elders’ to have one for every Fellowship Group. Fellowship Group leaders were appointed as well, and the Deacons became a separate group, including (for the first time) women. Their function was chiefly to work with, and understudy, the Pastoral Elders. There was no longer a regular combined meeting of Elders and Deacons. As the appointment of ‘Ministry Elders’ and ‘Pastoral Elders’ in 2000 was not a success it is not described here, and a completely new structure was introduced in 2005.

Opening the diaconate to women in 2000 led to an anomaly that was quietly overlooked. ‘Co-option’ to fill vacancies caused by death or resignation had always been part of the Chapel’s governance, and as people knew, or at least were reminded every five years, which men were full members and who were associate members, only full members were considered for co-option. However, as women’s names were not on the quinquennial ballot papers, their status was never a matter of public record – members were welcomed at communion services simply as ‘members’, without distinction. When it was noticed during the 2000-2005 diaconate that a lady associate member had been (unwittingly) co-opted to the newly structured Court, it was felt insensitive to say or do anything about it.

Opening the diaconate to women in 2000 led to an anomaly that was quietly overlooked. ‘Co-option’ to fill vacancies caused by death or resignation had always been part of the Chapel’s governance, and as people knew, or at least were reminded every five years, which men were full members and who were associate members, only full members were considered for co-option. However, as women’s names were not on the quinquennial ballot papers, their status was never a matter of public record – members were welcomed at communion services simply as ‘members’, without distinction. When it was noticed during the 2000-2005 diaconate that a lady associate member had been (unwittingly) co-opted to the newly structured Court, it was felt insensitive to say or do anything about it.

Election of 2005

Increasing work and family pressures meant that there were far fewer members with the time and qualifications necessary for leadership and other responsible roles in the congregation. The shortage of men willing and able to offer themselves for election as Elders at recent elections was further highlighted following the resignation of a number of Elders during the Court of 2000-2005. There was no way in which sufficient candidates could be found in 2005 to sustain the structure which had served the Chapel well, with only slight change, for 130 years. Furthermore, it was the recommendation of Christian Research in 2003 that the leadership of a church should not number more than 2.5% of the number from which they are drawn, and the Chapel’s traditional structure greatly exceed that.

The solution was believed to be a flatter organisational ‘pyramid’, i.e. a smaller leadership team but where the underlying responsibilities were more evenly and widely spread, thus easing the load on everyone. The ‘flatter pyramid’ involved a shorter line of responsibility, with decisions being taken by the person or committee appointed for the purpose rather than recommendations being taken to a ‘higher’ body for further discussion and approval.

The 2005 election put in place a unitary Court of Elders, aiming to elect about 12, i.e. under 2% of the total congregation and about 5% of the eligible male members. It was considered that this would provide a breadth of knowledge and experience and would constitute a workmanlike leadership group, allowing for adequate participation while not giving the appearance of an `inner circle’ or reverting to (as was claimed by the modernizes) the overlarge Court meetings of the past. At their first meeting, on 23 June 2005, they decided to drop the word ‘Court’ from Elders’ Court.

The Elders were to have a total overview of and ultimate responsibility for all aspects of church life. Elders were to be elected to rule (under Christ) and to lead the church. Their particular remit therefore included pulpit supply, public ministry, the admission, discipline and removal of members, the organisation and exercise of pastoral care, the approval of baptismal candidates and arrangement of Baptismal Services, strategic planning, the setting of remits for the Ministries, approval of major property changes and the appointment of the Deacons and Fellowship Group Leaders.

The day-to-day business management of the church became the responsibility of Deacons and Ministries, whose work was co-ordinated by the Deacons’ Court. An Elder had responsibility for overseeing, advising and guiding the Deacons in a Ministry, in respect of policy matters etc, but nothing in his involvement was to be construed as suggesting a direct management role by the individual Elder(s).

The Fellowship Group structure had become the main place for the provision of pastoral care in recent years and it was proposed that Fellowship Groups should continue in this role. The ‘day-to-day’ pastoral care within the Fellowship Groups was to be the responsibility of Fellowship Group Leaders, who would draw the attention of the Pastoral Team and the Elder to situations requiring action. This would take the place of the membership contact role of the 2000-2005 Pastoral Elders. An Elder was ‘attached’ to every Fellowship Group, so that while every member would continue to have ‘their’ Elder, and would continue to be able to call on his help if required, he would no longer have the direct routine contact with the member which had been the case previously. With the ratio of Elders to Fellowship Groups, it was obvious that several Elders would have more than one Fellowship Group within their area of responsibility. This did not preclude any member of the congregation approaching his or her Elder or a member of the Pastoral Team at any time on a matter of personal concern.

It was envisaged that the Deacons’ Court would meet as and when the Deacons decided but less frequently than on a monthly basis. It was not envisaged that the Deacons’ Court would approve and sanction all the actions of the Ministries, but rather act in a co-ordinating role and as a ‘sounding board’ for new or possibly contentious proposals. The Elders might attend the Deacons’ Court but the Senior Pastor, or his representative, was expected to attend the meeting.

The proposed (radical) changes were put a meeting of members on Thursday 3 March 2005, when the reasons for the proposals were carefully explained. A letter had gone to all members on 9th February, outlining the scheme. 163 votes were cast, 134 in favour and 29 against, giving 82.2% in favour (75% had been agreed before a change would be made.)

The role of the Church Secretary

Back to top of page

The relationship between spiritual leadership in the Chapel and administrative leadership began to change about ten years ago; prior to 1992, the pastoral team undertook only spiritual leadership in the Church, and the pastor’s salaried secretary dealt only with the pastor’s correspondence.

The entire running of the business side of the Church was looked after by lay people, headed by the Church Secretary, the Church Treasurer and the Deacons’ Court Secretary. This included keeping the membership roll, interviewing applicants for membership and baptism, administering the Pastoral Groups, arranging guest preachers when the pastor was away, deciding what went into the weekly Bulletin, carrying out staff appraisals and everything else of an administrative nature..

Peter Grainger, who became pastor in 1992, took over more and more of these functions; that is not a criticism, because during his pastorate fewer and fewer lay people were able to give the time, and to use their own business resources, to fulfil the traditional roles. It culminated in abolishing the position of Church Secretary in 2005.

We cannot – and do not want to – revert to the pre-1992 structure, but the Church Secretary performed three functions that do not seem to be so well covered in the new structure:

(1) keeping a supervisory eye on the whole administration; if anything was not done as it should have been, anywhere, he either noticed it or was told about it, and took steps to correct it. If anyone now has this bird’s-eye view of Church life, it is not well-known who it is.

(2) being available as a ‘lightning conductor’; that is different from the first point, which was actively seeing that things went well. This involved being known as the person to whom anyone seething with indignation could come, in the assurance that the concern would be looked into and an answer or explanation given. Now, it seems to me, one mentions a problem to the person or department concerned, and action may or may not be taken; if it is not, where does one go next?

(3) being at the door of the vestry after both services on Sundays, to be available to anyone, especially strangers, who wanted information about any aspect of Church life – because the Church Secretary was supposed to know where to point them if he did not know the answer himself.

Until 2000, the Church Secretary came into the pulpit about twenty minutes into both Sunday services and gave the Intimations. When Bill Walker became Secretary in 2000, it was on condition that he would not do this. It therefore became less obvious that the Church Secretary was the lynchpin in the administration of the Church, the first port of call for anyone with a concern about any aspect of Church life, and the person who was entitled to speak to anyone doing things in the Chapel that were ‘not in accordance with the tradition of the elders’.

APPENDIX ONE

LETTER SENT TO MEMBERS IN NOVEMBER, 1910.

Back to top of page

It has been resolved, in view of the expiry of the period for which the present officebearers were elected, that a new election will take place in November and December. Under the present constitution, the Elders are authorised to fix the number of officebearers; and in the exercise of this power they have fixed the number of Elders to be elected at six, and the number of Deacons at ten. The term of-office will be, as before, five years.

The following are the principal duties which have to be discharged by Elders:

- Visitation, under the direction of the Pastor;

- Attendance on the ordinances of the Lord’s Supper and Baptism;

- Conduct of the Weekly Prayer-Meeting in the absence of the Pastor;

- Distribution of the Fellowship Fund.

The Elders are also ex-officio Members of the Deacons’ Court. The duties of Deacons involve the charge and management of the Property and Funds of the Church, and of all Collections for the support of the Ministry and other purposes, with the exception of’ the Fellowship Fund. The Election of Elders will take place on 20th November and the Election of Deacons on 11th December. The accompanying Voting Paper is for the Election of Elders. The Voting Papers for the Election of Deacons will be sent out after the brethren have been elected for the Eldership; and the brethren elected for both offices will receive the right hand of fellowship on Sabbath 18th December.

Members are requested to write the names of the six brethren they consider most suitable for the office of the Eldership on the blank lines on the enclosed Voting Paper. The Voting paper (which should not be signed) must be folded and closed and be placed in the box at the Church door at the morning or evening Service on Sabbath 13th, or Sabbath, 20th November. If any of the members are unable to return the Voting papers on either of these days, they may be addressed to me at the Chapel on or before Sabbath 20th November. For the guidance of members a list of the eligible Male members of the Church is attached. The present Elders and Deacons are all eligible for re-election.

A. URQUHART, Secretary.

APPENDIX TWO

MINOR ALTERATIONS IN PROCEDURE

Back to top of page

The present procedure, namely sending a circular letter to all full members of the

Church, listing the names of male members over 21 years of age, and inviting

nominations from the list, originated in a discussion by the deacons on 3 February 1932. Only those who had signified their willingness to serve should be nominated, and at this stage of the scheme, the nomination had to be accompanied by the name of the proposer and seconder. In 1932, every existing office bearer was nominated for the post of elder, a total of 112. When it came to the election of Deacons, several who had been nominated did not reply to the communication from the Secretary as to whether they would stand for the office of Deacon. Decided that those who not replied should not appear on the voting paper.

There was a review in February 1950, before the quinquennial election that year. In consequence, the congregation was invited to nominate Elders and Deacons at the same time, on the understanding that if any man was nominated for Elder but not elected, he would automatically be given the opportunity of having his name added to the ballot paper for Deacons, if he so wished. With that alteration, the procedure followed at the previous election was followed.

268 nomination papers were returned. They named 68 members at least twice for the office of Elder and 24 more were named once only. All 68 were approached, and 32 indicated their willingness to stand for election.

The nomination papers (the combined paper) named 132 members at least twice for the office of Elder and 30 more were named once only. This meant that only 97 of the eligible male members were not nominated for some office, and that included 26 missionaries or others staying at a distance from the Chapel.

In consequence, the Deacons’ Court recommended that in future only those receiving four nominations should go forward to the vote.

There was a further review before the 1960 election. It was confirmed that no member under the age of eighteen could take part and that no member under twenty-one could be elected; that the list of the successful candidates would be announced in alphabetical order, not in order of highest to lowest votes; anyone could ask the scrutinisers how many votes they had achieved; twelve nominations were required for a name to go onto the ballot paper. A proposal to have one unified Court (still with elders and deacons, so the only practical differences would be that the deacons would decide who should be elders and the deacons would appoint the Church Secretary) received little support. They did however seek, and get, authority from a Church Meeting to increase the number of elders from sixteen to twenty, with power to co-opt four more, because of the increasing place of pastoral visitation; the number of deacons remained at eighteen, but with power to co-opt four more if needed.

For the 1960 election, 126 names were put to the congregation for elder, of whom 36 got the required twelve nominations. Twenty-six of these were prepared to go onto the ballot paper and twenty (the existing sixteen and four new ones) were elected. 141 names were put to the congregation for deacon, of whom 57 got the required twelve nominations, and those not elected as elder could be added to this list. Thirty-eight of these were prepared to go onto the ballot paper and eighteen were elected. Thirtyeight was twenty down on the previous (1955) election.