A Group which met weekly on Thursday afternoons in St Thomas’ Scottish Episcopal Church, Costorphine, Edinburgh, asked Ian Balfour in 2001 to give a Paper about evangelistic missions in Edinburgh, particularly those in which St Thomas had been involved. St Thomas was constituted as an Independent Chapel within the Anglican Church in 1844, and has a long and worthy history of contributing to interdenominational evangelistic outreach in Edinburgh, particularly since 1945 under its rectors Rev George Duncan, Rev Dr Geoffrey Bromily, Rev Philip Hacking, Rev Gordon Bridger, Rev John Wesson, Rev Dennis Lennon, Rev Mike Parker and Rev Ian Hopkins. This is the text of the Paper which Ian gave.

Scroll down or click sections

(click numbers to open/close additional notes)

- Introduction

- So to 1873

- 1881, the Second Moody and Sankey mission

- 1903, Reuben Torrey’s mission

- 1913, The Gipsy Smith Mission

- 1914, The Chapman–Alexander Mission

- 1924, return visit of Gipsy Rodney Smith

- 1955, All Scotland Crusade, with Billy Graham and soloist Beverley Shea

- 1965, Edinburgh Christian Crusade

This is not the story of the Edinburgh City Mission, which started in 1832 and which still does valuable Christian work, but an account of the years between 1873 and 1991, when Christians of many denominations in Edinburgh came together and arranged evangelistic Missions, latterly often called Crusades.

I’ve chosen six criteria for selecting which events to talk about and which ones not to include. We will look at the occasions when:

-

Christians of many denominations worked together

-

Invited a guest preacher

-

Planned a series of consecutive evangelistic meetings

-

Held them in a neutral venue (i.e., in non-church premises)

-

Made solo singing an integral part of the message

-

Had an ‘enquiry meeting’ at the end of the service

These were the characteristics of the Moody and Sankey Mission in 1873, and of a dozen or more subsequent Crusades until 1991. I’ll explain at the end why I’ve chosen 1991 for the last such occasion.

These criteria distinguish Missions/Crusades from other Christian activities. Obviously, there had been large evangelistic meetings in Edinburgh long before 1873. For example, from John Wesley’s Journal: ‘Sunday,

29 May 1763. I preached at seven in the High School yard, Edinburgh, … which drew together … an … abundance of the nobility and gentry, many of both sorts were present; but abundantly more at five in the afternoon. I spoke as plainly as ever I did in my life.’

That meets two of our criteria, a guest preacher and a neutral venue, but it wasn’t an interdenominational activity and it wasn’t a series – just morning and evening on the one day – there was no singing and no enquiry meeting.

Another area not covered is the many Rallies in neutral premises, for example in the Methodist Central Hall, when groups like Scripture Union, Christian Commandos, Youth for Christ, Youth With A Mission, and many more held evangelistic Rallies, particularly on Saturday evenings.

Back to top of page

What about the description ‘Revivals? The word Revival is used today in three different senses:

- First, with a capital R, it is used for spontaneous, sometimes fairly brief, outpourings of the Holy Spirit, often characterized by (a) anxiety about sin, (b) a wish to return to righteousness and (c) many conversions. On several occasions in Edinburgh, over the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, there has been Revival with a capital R, but that’s not our subject this afternoon.

- Second, revival with a small ‘r’. Following Revivals in 1905 and 1907 in Charlotte Chapel here in Edinburgh, the old building was demolished and replaced by the present one. At the opening of the new building in 1912, the church secretary said: ‘this one-time little congregation has … enjoyed an almost continual revival, witnessed almost continually men and women far down in sin being gloriously rescued and blessedly converted to God. And then, their crowning act of faith, the erection of this new church.’ That is a common use of the word ‘revival’ (r), to describe God’s blessing over a period of time in vibrant church life. That’s not our subject this afternoon, either.

- Third, the word ‘revival’ is sometimes used, more in America now than here, although it was used in this sense here at the beginning of the twentieth century, for ‘a planned evangelistic event’. American church notices may say: ‘There will be a revival here, next Sunday at 11 a.m.’, meaning a planned future event with a gospel message, culminating in an appeal. That has some of our six characteristics, it is planned and it is evangelistic, and it may have a guest preacher, but it is not inter-denominational and it is not in neutral premises.

So, to 1873

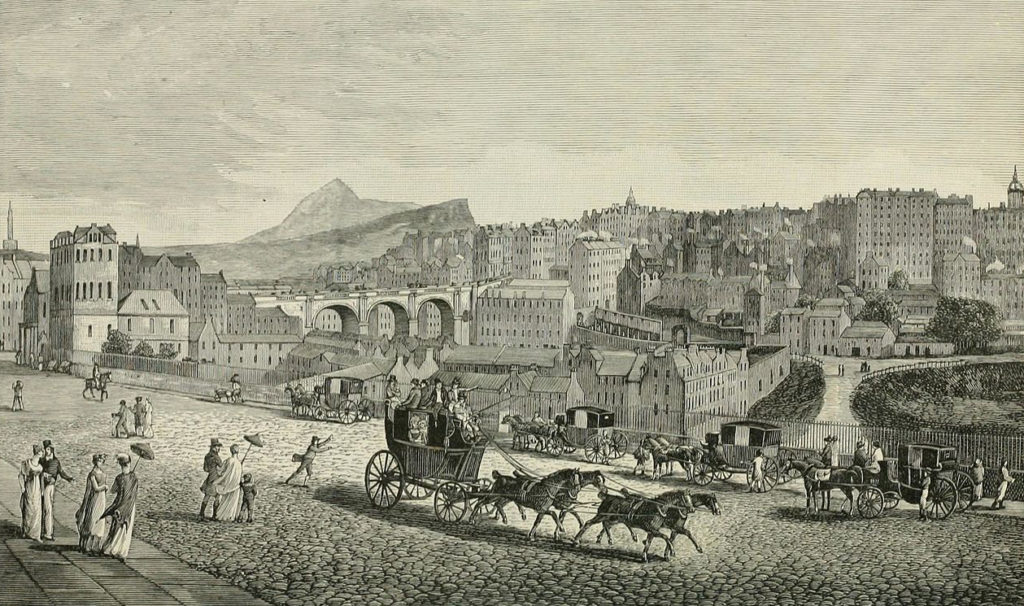

1873, when for the first time in Edinburgh a guest preacher and his soloist were invited to conduct a series of evangelistic meetings in a neutral venue (i.e., in non-church premises), supported by Christians of many denominations. This set a pattern that was followed for over a hundred years, as we will see.

In June 1873, two Americans, Dwight L. Moody (preacher) and Ira D. Sankey (soloist) landed at Liverpool, practically unknown. The two men who had invited them to England had both died before Moody and Sankey arrived, so no one met them and nothing had been arranged for them. They had a contact in York, and held a mission there. This led to other engagements in the north of England. An evangelical Leith minister heard about them from his brother in Sunderland and went to see for himself; he was so impressed that he invited the Americans to come to Edinburgh. He called together a local committee, representative of all the Protestant churches, to organize the campaign. They had only six weeks to make the preparations, and started by a daily prayer meeting at noon for ministers and laypeople. The first service was on Sunday 23 November 1873 in the Music Hall in George Street, but soon the Assembly Hall on the Mound, then the largest public building in Edinburgh, was crowded every evening, except Saturday, when there was a break.

There were four innovations, all of which took Edinburgh by surprise at first, but people soon warmed to them. The first was the advertisement that ‘Mr. Moody will (D. V.) preach the gospel, and Mr. Sankey will sing the gospel’.

Many/most here will remember when it was common in evangelical circles, to add the letters D.V. – Deo Volente, ‘in the will of God’ – to announcements, because James 4:13-17 chides those whose forward planning does not include the words, ‘If the Lord wills ….

Singing was not new in revival work, but for the first time Sankey made solo singing an integral part of the service. He accompanied himself on a small organ, borrowed from the Carrubbers Close Mission and returned to them when the campaign was over. (Some of you may remember the furore when the Mission sold it to an American organisation in.1960s). Sankey’s singing ‘struck home to hearers left unmoved by Moody’s preaching’ and many conversions were directly traceable to his singing.’ One of the stories worth repeating is how a favourite hymn of earlier generations, ‘There were ninety and nine that safely lay, in the shelter of the fold …’ became popular. The evangelists had been in Glasgow and at the station on the way back, Sankey bought a local evening newspaper. When on the train, Moody asked for time to prepare for the evening rally, so Sankey glanced through the newspaper. He was taken with a poem and so cut it out and put it in his wallet. A few nights later, after Moody had preached on the parable of the Lost Sheep, he then turned to Sankey and asked him to sing an appropriate concluding song. Sankey pulled the cutting from his wallet, put it on the music-stand, and began to sing – impromptu, which is why the tune is so ‘tuneless’. Having completed the first verse, he had to remember the music he had just composed and repeat it for the other verses. It was so well received that it was soon included in hymnbooks and was a favourite at evangelistic meetings for much of the first part of the twentieth century.

Singing was not new in revival work, but for the first time Sankey made solo singing an integral part of the service. He accompanied himself on a small organ, borrowed from the Carrubbers Close Mission and returned to them when the campaign was over. (Some of you may remember the furore when the Mission sold it to an American organisation in.1960s). Sankey’s singing ‘struck home to hearers left unmoved by Moody’s preaching’ and many conversions were directly traceable to his singing.’ One of the stories worth repeating is how a favourite hymn of earlier generations, ‘There were ninety and nine that safely lay, in the shelter of the fold …’ became popular. The evangelists had been in Glasgow and at the station on the way back, Sankey bought a local evening newspaper. When on the train, Moody asked for time to prepare for the evening rally, so Sankey glanced through the newspaper. He was taken with a poem and so cut it out and put it in his wallet. A few nights later, after Moody had preached on the parable of the Lost Sheep, he then turned to Sankey and asked him to sing an appropriate concluding song. Sankey pulled the cutting from his wallet, put it on the music-stand, and began to sing – impromptu, which is why the tune is so ‘tuneless’. Having completed the first verse, he had to remember the music he had just composed and repeat it for the other verses. It was so well received that it was soon included in hymnbooks and was a favourite at evangelistic meetings for much of the first part of the twentieth century.

The second innovation was that Moody stressed the joys of heaven and the love of God, demonstrated at Calvary; contemporary evangelists preached more on hell and judgement.

The third innovation was written requests for prayer, either by people themselves or by relatives and friends; the requests were read out by the preacher and responded to by people in prayer. Those who were ‘anxious’ (that is, concerned about their spiritual state), were invited to say so, and concerted prayer was offered for them.

The fourth novelty was the ‘enquiry meeting’ at the end of the service, for those whose conscience had been awakened by the message. Experienced Christians personally counselled them and ‘Decisions for Christ’ became the watchword of the campaign. The Campaign continued from 23 November 1873 to 21 January, two months. At the concluding meeting for converts only, 1700 were present, including a young solicitor, Andrew Urquhart, who had been converted during the Crusade and who became the saviour of Charlotte Chapel when there was serious talk in 1900 about disbanding the congregation and closing the building. The permanent effect of the mission, apart from individual conversions, was that Sunday services in many churches became more ‘user-friendly’. After the first edition of the hymnbook Sankey’s Sacred Songs and Solos came out – one penny for the words, sixpence for the music edition – Sankey’s gospel songs were sung in homes, although not yet in church services, all over the whole country.

1881, the Second Moody and Sankey mission

Back to top of page

Moody and Sankey returned to Edinburgh by invitation in 1881, for a campaign that lasted six weeks. This time it was held in the Corn Exchange. Many came to the Saviour, but not on the scale of the 1873-4 visit. There was, however, one

outcome of their second visit that has been a feature of Edinburgh evangelical life ever since. During the campaign, Moody heard that Carrubbers Close Mission, off the High Street, held an open-air meeting every evening of the year. He paid a surprise visit to one of these meetings and was greatly impressed. He was told that the work of Carrubbers could be extended if they had better premises. He set about personally collecting £10,000 for a site and a new building, and he personally laid the foundation stone of the present building at 65 High Street in 1883. A year later, in 1884, he opened the premises and preached on the text, ‘Come unto me all ye that labour and are heavy laden and I will give you rest.’ The present internal layout dates from the late twentieth century, and the name is now Carrubbers Christian Centre.

1903, Reuben Torrey’s mission

Back to top of page

The next citywide mission of which I am aware, and which meets the six criteria set out, was in February 1903. An American evangelist, Reuben Torrey, conducted a four-week mission in the Empire Theatre. One convert, a railwayman, who was still active at open-air meetings fifty-five years later, loved to tell how he had gone forward in response to Dr Torrey’s appeal, and how Torrey gave him a Bible, inscribed with the words:

Read daily your Bible if you would be strong

To witness for Jesus and overcome wrong;

The Author and Book will surely abide,

But they who neglect it will surely backslide.

One feature of this 1903 mission is worth noting – appealing directly to children for conversion.

Fresh ground was opened up by the evangelist on Friday afternoon [of the third week], when the Central Hall, Tollcross, was packed from floor to ceiling with young people from all ages and classes. The scripture lesson consisted of memorising Isaiah 53 v 5, ‘He was wounded for our transgressions’; after this had been done, ‘our’ was changed to ‘my’.

He was wounded for my transgressions’After every precaution was taken to prevent boys and girls from simply following one another impulsively, about three hundred professed to accept the Lord Jesus Christ as Saviour. Particularly touching was the testimony of a nine-year-old girl, whose father had previously protested against children being encouraged to go into the inquiry room. She begged him for leave to go in, because ‘He was wounded for my transgressions’.

1913, The Gipsy Smith Mission

Back to top of page

‘Gipsy’ Rodney Smith (1860-1947) was a much-loved evangelist. Born in a gypsy tent near London, he had no education. His father was in and out of jail, and first heard the gospel from a prison chaplain; when he was released from prison, he asked where a gospel meeting might be found, and took his six children to the local Mission. The father was converted and later sixteen-year-old Rodney, partly through hearing Ira Sankey sing. He was illiterate, but said: ‘One day I’ll be able to read and I’m going to preach too. God has called me to preach.’

He taught himself to read and write and began to practice preaching. One day at a Salvation Army meeting, William Booth asked the young lad to say something. Rodney sang a solo and gave his testimony. Booth asked him to become an evangelist, and he travelled widely. In 1913, the Edinburgh Evangelistic Association invited him to conduct a mission in the Assembly Hall on the Mound from Sunday 2 to Wednesday 12 March 1913. Thousands flocked to hear him, and hundreds were unable to get in. As many men were turned away from the Sunday afternoon meetings for men only as would have filled the hall twice over. The inquiry room was filled daily with seeking souls.

At a meeting for converts – note the parallel with Moody in 1873 – 120 were present. Mature Christians offered advice on how to grow in the faith, under three headings: (1) Good food (Bible study), (2) Good air (prayer) and (3) Good exercise (Christian service). Gipsy Smith was later awarded an O.B.E. for his services as an evangelist.

1914, The Chapman–Alexander Mission

Back to top of page

John Wilbur Chapman (1859-1918) was an American Presbyterian. He is best remembered as an evangelist, but he was also the author of:

One day when heaven was filled with His praises, One day when sin was as black as could be, … Chorus: Living, He loved me; dying, He saved me; Buried, He carried my sins far away,

Chapman teamed up with Charles Alexander (1867-1920), another American, a soloist – note the continuing practice, introduced by Moody, of having a guest soloist as well as a guest preacher – still the pattern with Beverley Shea singing with Billy Graham in the 1950s, and many more. In 1913 Chapman and Alexander were asked by the Edinburgh Evangelistic Association to hold a preliminary mission in the Assembly Hall for several weeks, followed by the main mission n the Olympia Palace Picture House (Cinema), in Annandale Street, off Leith Walk, from 4 February to 4 March. A huge redbrick garage for Edinburgh city buses now occupies the site.

Chapman was dignified and serious in his preaching, but ‘Charlie’ Alexander, as he was called, ‘warmed up’ the audience with jovial humour and lively singing. His style was copied by many others, and has continued to influence the pattern of evangelistic meetings – someone to come on and get the audience into a good mood before the preaching.

A contemporary report of the Mission, while it was still in progress, read:

What shall we say about the Chapman–Alexander Mission? Unprecedented crowds. Preaching full of convicting power. Hundreds dealt with. All classes and conditions present. Great singing. Many, both saints and sinners, blessed. Cannot describe the scenes and the experiences. Wonderful. Prayers answered. Hearts cheered. Homes and lives changed. Glory be to God. And the tide is rising.

The Committee advertised the services in Olympia as ‘5,000 comfortable seats – grand music’. In writing the history of the Olympia Palace Picture House (the cinema in Annandale Street), an Edinburgh historian, George Baird, recently ridiculed the advertisement of 5,000 seats as ‘poetic licence’ or ‘kidology’’. He maintained that the Cinema sat only 1,800. But the Mission shows how there can be two different answers to the same question. There was such interest in the Mission that Chapman preached six times a day, so even if one ‘sitting’ could accommodate only 1,800, during one day at the Olympia, there was ample scope for 5,000 to hear him preach in a series of services.

Christian counsellors, who met with enquirers at the close of the meetings, were issued with a supply of covenant cards, perforated into two parts. The first was a record of the ‘Decision’ made and was given to the new believer; the bottom part was sent to the church of the enquirer’s preference, so that they could follow it up.

Some churches continued to use Alexander’s Hymnbook No. 3, which had been the mission songbook, at their evening (evangelistic) services for many, many years.

1924, return visit of Gipsy Rodney Smith

Back to top of page

The Edinburgh Evangelistic Association, which had invited Gipsy Smith for the mission in the Assembly Hall in 1913, renamed itself the Edinburgh Evangelistic Union in November 1924, with two hundred Edinburgh ministers and Christian workers in membership. One of its first activities was to arrange a return visit of Gipsy Smith in April and May 1925. Lunchtime and evening meetings in St Cuthbert’s Church on weekdays were attended by over two thousand, and Sunday services in the Usher Hall, at 3 p.m. and 8 p.m., attracted three thousand a time, plus an overflow.

I don’t have details of any other citywide, interdenominational Crusade between the end of the First World War in 1918 and the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939; perhaps some of you can help me on that? My father spoke about Bryan Green, a Church of England rector and a passionate evangelist, who in the early 1930s was one of the youngest speakers to address the Keswick Convention; he came to Edinburgh for a series of evangelistic meetings, but where and under whose auspices I do not know.

An Irish evangelist, William Patteson Nicholson (1876-1962) was invited to conduct a Campaign in the Assembly Hall on the Mound in the late 1940s. He was known for his blunt language and some went to hear him just for that. The leader of our Covenanter Class – we had a class before church on Sunday mornings – told us that he had been at one of the meetings and that ‘WP’ had asked, ‘Is there anyone here who has never quarrelled with his wife? Half a dozen men sheepishly stood up, and Nicholson said: ‘Remain standing, and the rest of us will pray for these liars’. Ten of his sermons may be heard at

http://www.sermonaudio.com/search.asp?SpeakerOnly=true&currSection=sermonsspeaker&Keyword=William^P.^Nicholson

Roy Hessian held a Crusade/Mission in the Usher Hall, early in 1946. He is perhaps best known for his 1950 book, The Calvary Road, but I remember him particularly because one of the boys in my class at school, Geoffrey Oliver, knowing that I came from a Christian home, asked me in 1946 whether I had been to any of the meetings? I said that I had been a couple of times, to which he replied that he had been every night and at one of the meetings he had become a Christian. Then there was the Tom Rees Crusade in the Usher Hall in 1953; as he stayed with my parents for the duration of the Crusade, I was there every night as chauffeur – one could park without difficulty at the front door of the Usher Hall in 1953. He had powerful messages, initially challenging Christians and, as they became enthusiastic and brought their friends, encouraging many to come to the front for counselling and conversion.

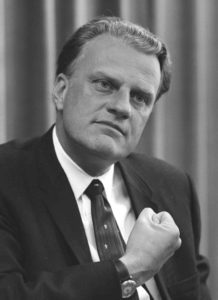

1955, All Scotland Crusade, with Billy Graham and soloist Beverley Shea

Back to top of page

Although Billy Graham spoke only twice at public meetings in Edinburgh during the 1955 All Scotland Crusade – the main meetings were in Glasgow, and special buses and trains were laid on every afternoon for travel from Edinburgh to the Kelvin Hall there – it qualifies for inclusion in Edinburgh citywide Crusades for two reasons. First, the organisers asked Edinburgh Christians to form special prayer groups, including several all-night prayer meetings. The first of these was on

Friday 18 March 1955, and seven hundred were present for the start at 10 p.m. There were four sessions of two hours, with a break for light refreshments at 2 a.m. ‘The tide of prayer flowed spontaneous and free. It was an inspiration to be present. Our oneness in Christ, though all denominations were represented, was abundantly manifest.’ Five hundred were still present and participating when the meeting concluded at 6 a.m. Two similar nights were held on Fridays 1 and 22 April. There was also a daily central meeting for prayer at lunchtime throughout the month of April.

Secondly, the All Scotland Crusade qualifies for mention here because on Wednesday 20 April the evangelists and their team appeared personally at Tynecastle Park, the home of the Heart of Midlothian Football Club, for a rally at 2 p.m. Twenty thousand (including me) were present and after a service lasting for 90 minutes, 922 came forward and recorded their decisions for Christ. Two days later, Billy Graham spoke to students in the McEwan Hall, at which I was also present. (In the committee room, preparatory to the meeting, someone asked Billy Graham how he prepared to address an audience of students. He replied, ‘As I do to speak to my Sunday School class.’

For the last ten days of the All Scotland Crusade, there were audio relays from the Kelvin Hall to forty centres throughout Scotland, including Edinburgh.

1965, Edinburgh Christian Crusade

Back to top of page

On his arrival in Edinburgh, as the new minister of Charlotte Chapel, Alan Redpath proposed holding a citywide evangelistic crusade for three weeks in the autumn of 1965. He had a speaker and a committee already in his mind, with Philip Hacking (Rector of St Thomas) as chairman, but he was anxious that it should be an inter-church effort. The Edinburgh Evangelistic Union was renamed the Edinburgh Evangelical Council, and Stephen Olford from New York was invited. He asked to have Bill Hoyt, who had a lot of Red Indian blood in him, as the soloist. I was the Crusade Secretary and when I suggested to Stephen Olford that he consider one of the many good soloists in the country (to avoid expense), he said that it was crucial to have a soloist who had worked with him and understood his methods – like Moody and Sankey.

Meetings were held in the Usher Hall for 19 evenings in October 1965, nightly except for Friday, when the Scottish National Orchestra had a prior booking. Well over two thousand attended every evening, with a closed-circuit television overflow to a nearby church at the weekends. The public meetings attracted 46,000 people in total, of whom 1,200 were counselled, most of them young, and about half of them made a first-time profession of faith. Inquirers were referred to a church of their choice for follow-up.

Trying to publicise the Crusade gave me an insight into the mind of the secular Press. I contacted all the local newspapers to suggest that an event which was filling the Usher Hall to overflowing night after night was worth at least a mention in their paper. Not a word was printed until the minister of the nearby Unitarian church in Castle Terrace told the Edinburgh Evening News that he had attended one night and that Stephen Olford’s preaching reminded him of Hitler. That made the front page, and my effort to answer it in a subsequent edition was ignored.

Before coming to the last Crusade to be described in this Paper, the 1991 Billy Graham Crusade, I should say a word about (a) Arthur Blessit, who travelled round the country pulling a large wooden Cross and who held a series of evangelistic meetings in the Assembly Hall, (b) Dick Saunders’ several annual tent campaigns in the Meadows, (c) Luis Palau, and others. The reason for not saying more about them is that they don’t fit our criteria of ‘Christians of many denominations working together’. Groups of interested Edinburgh people invited these evangelists, but they were not truly inter-denominational efforts.

Billy Graham conducted Mission Scotland 1991, including two afternoon rallies at Murrayfield; at the conclusion of the Mission, he invited everyone who had been involved to meet him in the Tron Church in Glasgow. I was there, and the building was packed. Billy Graham said how much he appreciated being in Scotland and encouraged those present to plan for a return visit of himself and his team. Talking to people afterward, it was clear that the citywide, multi-church, interdenominational, evangelistic Crusade had had its day, and now, a decade later, I can safely say that we will not see its like again in our lifetime. The enormous energies which were poured into these ventures are now being used to evangelise through Home Groups, ‘friendship evangelism’, welfare organisations like Bethany and many, many others in more modest ways.

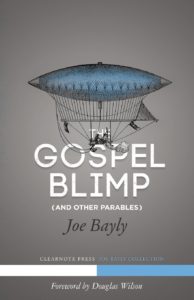

Let me finish by mentioning a book, now made into a film, called ‘The Gospel Blimp’ (American for an airship). In the imaginary story, a young couple were concerned to evangelise their neighbourhood. When they saw a blimp cruising overhead, they got the idea of purchasing one, flying it around their city with gospel texts on banners behind it, broadcasting Christian music and dropping leaflets with gospel messages. They got a group of friends together, raised the funds, bought a blimp and hired a pilot. For months they put all their energies into this novel method of evangelism, without seeing a single response. One day the blimp broke down. With time on their hands, they held a barbecue in their garden and invited some neighbours. To their astonishment, when they said that they would like to talk to the neighbours about Jesus, the neighbours replied that they would love to do just that, but that the couple had obviously been so busy over recent months that the neighbours had never been able to catch them at home to have a chat.

Let me finish by mentioning a book, now made into a film, called ‘The Gospel Blimp’ (American for an airship). In the imaginary story, a young couple were concerned to evangelise their neighbourhood. When they saw a blimp cruising overhead, they got the idea of purchasing one, flying it around their city with gospel texts on banners behind it, broadcasting Christian music and dropping leaflets with gospel messages. They got a group of friends together, raised the funds, bought a blimp and hired a pilot. For months they put all their energies into this novel method of evangelism, without seeing a single response. One day the blimp broke down. With time on their hands, they held a barbecue in their garden and invited some neighbours. To their astonishment, when they said that they would like to talk to the neighbours about Jesus, the neighbours replied that they would love to do just that, but that the couple had obviously been so busy over recent months that the neighbours had never been able to catch them at home to have a chat.

Back to top of page